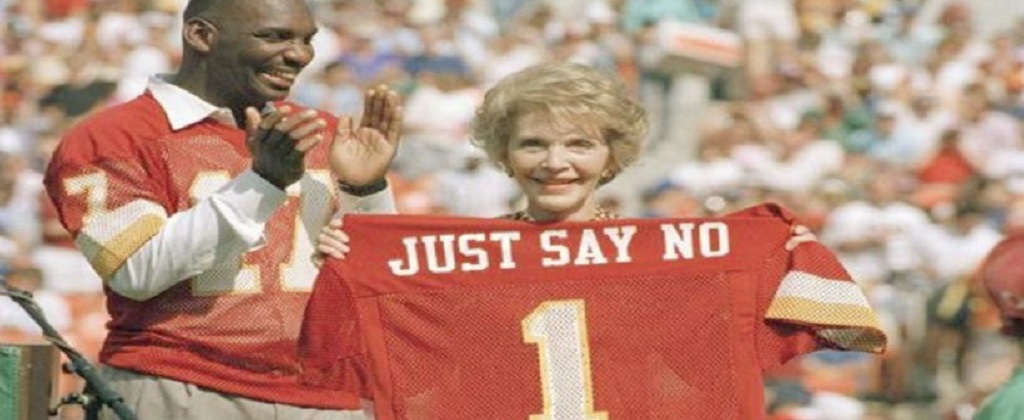

The 1980s “Just Say No” anti-drug campaign, popularized by former First Lady Nancy Reagan, was a defining effort in the war on drugs. Despite its visibility and influence, the campaign failed to significantly curb substance use among youth. Its shortcomings are clear, but what is often overlooked is how qualitative research methods could have transformed its approach and impact.

To design an effective public health communication campaign, health communicators must deeply understand the audience’s motivations, behaviors, and cultural contexts. Unlike quantitative methods, which rely on numbers and statistical patterns, qualitative research digs into the “why” behind human behavior, providing rich insights that can inform messaging and strategies. If the “Just Say No” campaign had leveraged some of these qualitative methods, the outcomes may have been very different.

Understanding Youth Through Focus Groups and Interviews

At the heart of any successful health communication campaign is a clear understanding of the target audience. The “Just Say No” campaign primarily targeted youth, a group with diverse social, cultural, and psychological factors driving their behaviors. Qualitative research methods such as focus groups and in-depth interviews could have allowed campaign designers to better understand why young people experimented with drugs and what barriers they faced in resisting peer pressure.

Focus groups, for example, could have revealed the nuances of peer influence, stress, and curiosity that contribute to drug use. By creating a space where young people felt comfortable sharing their perspectives, researchers could have gathered invaluable insights into the real challenges they faced. These insights would allow for the creation of messages that resonated more deeply and addressed the underlying factors leading to drug use, rather than simply instructing youth to say no.

Crafting Messages That Resonate

The “Just Say No” campaign’s simple and direct message was memorable, but it lacked the nuance needed to shift behavior in the long term. Messages that resonate acknowledge and address the complexity of audiences’ social, cultural, and psychological backgrounds. Qualitative methods, such as thematic analysis of interviews or focus group data, could have helped develop more sophisticated messaging that speaks to the emotions, concerns, and aspirations of youth.

For example, by exploring the real-life contexts in which young people were exposed to drugs—whether through family, friends, or social environments—campaign designers could have crafted messages that spoke directly to those circumstances. The campaign could have provided practical, relatable strategies for dealing with peer pressure, framing refusal not as a simple rejection but as a positive choice aligned with their personal values and goals.