This blog was written by Cooper Smitherman, Communication and Culture's Social Media Intern. An English and Psychology undergraduate at the University of Alabama in Huntsville, Cooper channels his passion and his skills for writing and research into social justice efforts.

How did “Abstinence-Only” Sex Education campaigns take control of HIV discourse for so long? The answer lies in the way AIDS upturned the historical and cultural landscape of the United States in the 1980s and 1990s.

In a previous article for this series, “The Historical Foundation Behind the Successful “HIV Stops With Me” Health Communication Campaign,” we explored how this campaign situated itself at the forefront of a rapidly changing public attitude toward HIV/AIDS. However, this campaign responded to years of inadequate sex education arising from the widespread panic of the 1980s HIV/AIDS crisis.

During this time, abstinence was publicly preached as the preferred form of STD prevention, which was an ignorant solution that did not respond to individual needs, preferences, and beliefs. Additionally, anti-LGBTQ rhetoric dominated headlines and public policy due to inaccurate public perceptions of HIV transmission.

When AIDS diagnoses first started to rise in the early 1980s, the primary affected demographic was gay men (Grimes 86). However, Dr. David J. Sencer (New York City’s Health Commissioner at the time) insisted that other groups were being diagnosed as well, including heterosexual drug abusers and Haitian immigrants (86). The cause and symptoms of the disease were still largely unknown by the time hospitals had become overrun with patients diagnosed with HIV/AIDS (86).

This troubling development ultimately created a major public health problem that posed no immediate solutions. In the absence of potential hope, the country became a breeding ground for negative health recommendations to explain the crisis at hand.

In other words, many felt a scapegoat was necessary in order to alleviate the growing tension surrounding AIDS. Once the epidemic had exceeded two years in length with “still no end in sight,” the public had become restless in finding solutions (138). Given that, in 1981, the initial group of 41 U.S. patients believed to have AIDS were all gay men, many believed this was a logical starting place for addressing the epidemic (135, 137).

Public policy reflected and even encouraged this incorrect belief before the AIDS epidemic had reached broader significance. For example, in 1981, the Reagan administration passed the Adolescent Family Life Act (AFLA), which provided funding for organizations to promote “chastity and self-discipline” as the only correct form of sexual safety (KFF).

Additionally, news reports centered around AIDS quickly transformed from scientific writing styles to more narrative writing styles to mystify the virus.

For example, on August 8th, 1982, Robin Herman’s “A Disease’s Spread Provokes Anxiety,” a New York Times article, included numerous statistics-based facts and developments surrounding the spread of AIDS and even acknowledged that “panic behavior” and speculation would set in sooner rather than later (Grimes 86).

Just a few months later, on February 6, 1983, Robin Marantz Henig’s “AIDS: A New Disease’s Deadly Odyssey,” also a New York Times article, portrayed the disease as “the mysterious AIDS organism” and even made sure to establish “promiscuous” gay men as the first patients with AIDS (137). In another example, Henig quotes the following from Dr. Dan William: “It’s important for a patient to emphasize to his sex contact that he must not bring any diseases home with him” (138).

While Henig’s article does raise important points about the true nature of the virus and initially appears harmless, she leaves room for reasonable doubt with her delivery.

Rather than discussing AIDS in a purely scientific manner, Henig opts to maximize entertainment value by characterizing the virus as a mystery unlike any other to be solved by a righteous detective. She subtly suggests promiscuity, particularly among gay men, as a leading cause for the epidemic, while not-so-subtly affirming this false belief from a medical voice who “counsels monogamy” (138).

Through this one article driven by the increased onset of AIDS, a new American culture was evident: fear of the LGBTQ community was instilled and abstinence-only sex education became an actionable yet heavily flawed public health solution in a post-AIDS United States. Guided by panic over science, public policy followed suit and, indeed, had been following suit long before Henig wrote her article.

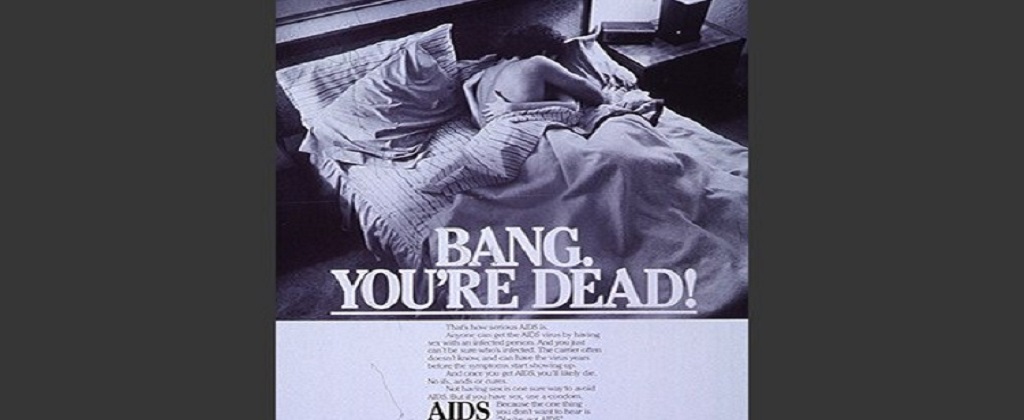

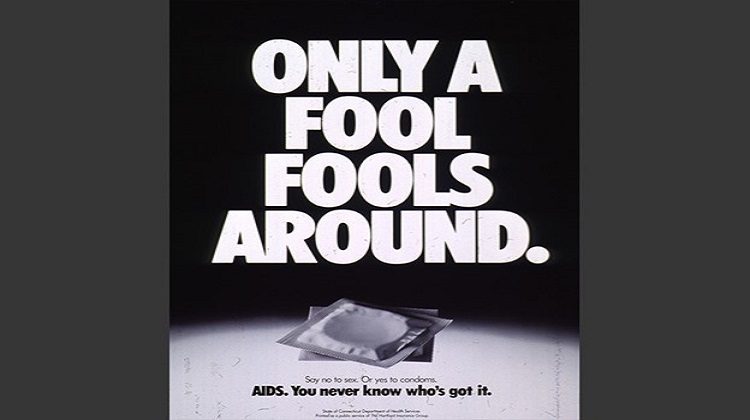

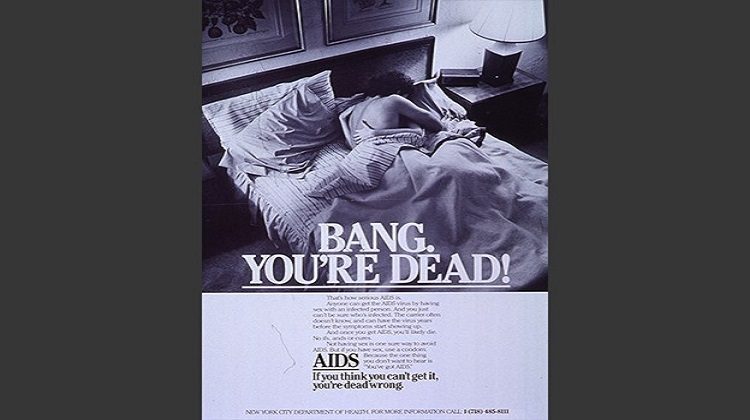

In this new United States, incorrect and deeply offensive health messages (such as the ones pictured below) thrived.